Manipulating celluloid

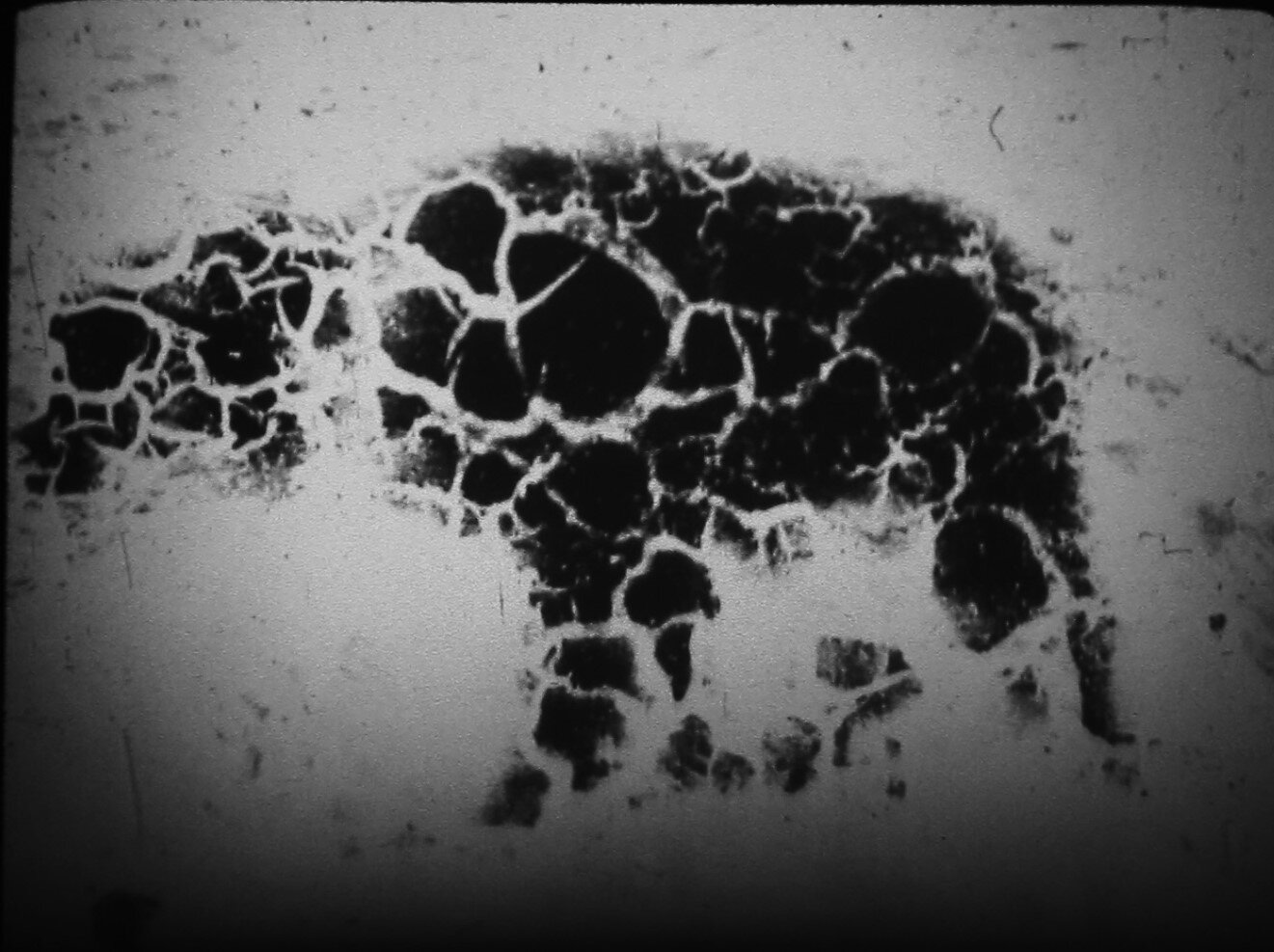

Still from Sir Bailey, by Matt Ripplinger

An interview with Matthew Ripplinger

By Jason Britski

Matthew Ripplinger is an emerging experimental filmmaker based in Regina, Saskatchewan. His interests focus on black and white 16mm and 8mm film, hand processing, contact printing, optical printing, and home-made emulsion. At press time, his film Sir Baileyhas screened at 15 film festivals in six countries. Aside from creating his own independent avant-garde films, he also works as a cinematographer in both fiction and documentary. In addition, Matthew works in the medium of printmaking, and explores themes and processes combining the mediums of analogue film and print work.

Jason Britski: Can you tell me a little bit about Sir Bailey? Where did the idea come from?

Matthew Ripplinger: The idea for Sir Bailey came to me when my family and I had to face the hard reality that my dog – that I had grown up with – had become sick and was not going to be around for much longer. This film is a way of paying tribute to one of my dogs, Bailey, through my own artistic endeavors. The analogue film suits this project as it creates a physical connection to a physical being I have been around since my childhood. What I wanted to do was make a film that wasn't completely sentimental, that would have a conflict at its centre – the conflict being Bailey fighting the bone cancer that he was suffering from. Since I am really interested in avant-garde film, process cinema, and different analogue techniques involving chemistry, I felt like this was the project where I could really elevate my research in that field.

JB: Can you elaborate on your process?

MR: I had three short shooting days with my dogs Bailey and Brooke. I even brought them to the production studio at the (University of Regina). On the last day of our dogs’ lives, I grabbed a Bolex and lights from the film department, and captured some shots of Bailey in our home during his last few hours of life. This is where the majority of the film is sourced. He could hardly stand. It took a lot of encouragement to have him get up and walk around for one of the shots in my film. I kept the filming brief, as I wanted to let him relax in these moments and be present with my family. At this point I wasn’t exactly sure what I would do with this footage. But I knew that I wanted to work with the theme of decay, loss, and suffering through a physical connection by manipulating the celluloid through photo-chemical means.

The technique that I came across was homemade emulsion. I came across this technique in experimental film handbooks and by viewing filmmaking workshops online, and did a lot of research. I was exposed to filmmakers like Lindsay McIntyre, Alex McKenzie, and Esther Urlus through an experimental film class, as well as my own research. To me, it is a really unique thing that very few people are doing.

JB: So, this technique was all self-taught? You didn’t have any help in figuring out how to do it?

MR: Yes, I basically taught myself how to brew the emulsion. Although many filmmakers before me laid the groundwork. Without them I would not have known where to begin. I needed an extra hand in making the emulsion during my first few trials. My friends and fellow filmmakers Elian Mikkola and Jeffrey Altwasser initially assisted me with mixing the chemistry. I followed the recipe and steps from Esther Urlus’ book Re:inventing the Pioneer. She includes a detailed description of how to make emulsion, as well as different kinds that yield faster, or slower film speeds. The one I made is a basic emulsion recipe that yields an ISO of one or lower. I don't think you could really expose it through a camera at 24fps, and the delicate nature of the emulsion would risk breaking off of the base. I would contact print from my camera negatives in strips of a little more than a foot in length. That's the best way to do it because if the emulsion strip fails, I can always go back to my negative and try again. So, I used Esther’s recipe, and did a lot of trial and error. It takes maybe a day or two to make the emulsion.The most difficult step is the emulsification, where the silver nitrate and the potassium bromide solutions must be mixed very slowly, and in the dark. Through multiple trials, I was able to arrive at a process to make it on my own. The other step, which is quite difficult, is the reticulation process. This shifts the metals in the emulsion and distorts the photographic image by heating up the film. Where the trial and error occurred was in terms of the best way to apply the emulsion onto the film, and what clear leader, or recycled film, would be the best material to use. That took a couple of days, and then once I figured it out and got a good exposure and contrast with the film, I decided that it wasn't abstract enough. So, I experimented with different heating temperatures for reticulation – and different ways of applying the emulsion as well. I was using a brush to paint on the film base, trying different ways of painting with a brush, and experimenting with how much emulsion to coat the film with. In the end, it took months to get the reticulation results that I wanted.

JB: How do you feel about it now? Are you happy with the results?

MR: I’m very happy with the way the film turned out. There are things I would like to have added, or tried to expand on in terms of my process. I did try putting Bailey’s ashes on the film, on the emulsion, and adding him directly on to film. But I didn't get the look that I wanted, and I was running out of time with the deadline for the project to be finished, so I stuck with what I knew and I could work with for the best results, and went forward with that. As for the finished film I am quite satisfied.

JB: Can you tell me a little about the importance of the audio design and the soundtrack? The first time I saw it screened it was silent. I was really struck by what you did with the sound once the film was finished, and the continued work with the imagery. There was a lot more work put into it that really elevated the film in terms of both picture and sound. It really is a striking film.

MR: At my senior year screening I showed a silent version through digital means, because I didn't have a soundtrack ready at that point, nor was the film ready to be made into a print. I liked the silent screening at the Artesian, because the atmosphere and the environment still carry sounds throughout the space. It was interesting to hear sounds from inside and outside the room during the screening, even though they didn't really relate to the film at all.

After the 4th Year screening I went back to work as there were some more shots I needed to add, and more optical printing to do in order to make a final print of Sir Bailey, because that was the main objective for my film. After Ispent many nights at the Filmpool working on the optical printer, and then I would take the film home and process it, and take it back to the Filmpool to work on the Steenbeck. I probably spent an extra two weeks with the optical printer, and then a little less than a month editing it. There are some things I would’ve loved to add, or maybe one shot I would have liked to have left a little longer, but I just didn’t have the image. It just didn't exist. Some editing techniques I used were graphic matches, and cutting on action – not necessarily the action of what Bailey was doing on screen, but the action of the celluloid, and how the celluloid was shifting and distorting; it could transition into another shot, and maintain that fluidity. I worked on the soundtrack throughout the summer.

For the sound design I wanted to include as much of Bailey’s sounds as I could. I included “found” sounds of Bailey walking across the hardwood floor at my parent’s house, and I also added the sound of his bowls that he would eat and drink from. I recorded the bowls as I rubbed them together to create a metal, not necessarily an industrial sound, but some kind of droning sound. I wanted to use items that he interacted with to have him more physically present in the film. There was also a lot of sound manipulation, echoing, and using reverb for the bowls. The sound of Bailey’s breathing is also in there. I would stretch most of the sounds out to elongate the tones. I used his heartbeat as a motif for the tension present in the film in matching the velocity of the movement, and the pacing of visuals. Basically, me running out of time to spend with my dog.

JB: Were there any other sources of inspiration in terms of how you created this film?

MR: The very first film production class I took was taught by Mike Rollo. He exposed me to all kinds of experimental and avant-garde films, and introduced me to techniques such as hand processing and contact printing. I have been very inspired by filmmakers like Peter Tscherkassky, Paul Sharits, Francois Miron, and Esther Urlus. There was a class assignment with the Bolex – shooting with 16mm film. It took a couple weeks to get the film processed, but when it came back I was blown away by the look of the projected black and white film. It has a very organic look.

Before I was even interested in film, I was enrolled in the science department focusing on chemistry. I'm not even sure what field of chemistry I was really interested in, but I knew I liked the idea of mixing chemicals to create new compounds and trying different formulas. I also like the fact that what I might be trying to achieve through the film will turn into something I didn’t expect. Mike showed me a lot in terms of how to process and experiment with film. He showed me the G3 tank and how to process 16mm film, and that's when I made the first film that I shot on film, Dr. Ripp, which I hand processed. That was a really good starting point. One great experience (that I had making) Dr Rippwas that I was able to go to a film festival in New York called New Filmmakers which showcases emerging filmmakers’ work. The venue was the Anthology Film Archive – there's so much history in that space. They preserve all the film prints from all these experimental filmmakers from the American underground avant-garde era. Maya Daren used to live in that building. Apparently, they still have the sink she used. The screening went really well, and I did get to go up on stage for a Q & A.

JB: You recently got back from a film festival in Scotland. Can you tell me how your experience has been, screening the film in other cities and countries?

MR: Sir Bailey premiered at WNDX in Winnipeg, and that went really well. I was able to (attend), and it was a great experience to see it on film in a theater for the first time. Everyone is so nice in Winnipeg, and they have a great experimental film community.

After that, it screened a few times in Regina – at the SIFAs, where it was awarded a technical achievement award, and then screened at the Pile of Bones Underground Film Festival; at Antimatter; and then it made a run in the states at Athens International and Chicago Underground Film Festival. The most recent screening was at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in Scotland. That was so much fun. It was one of the greatest experiences that I have had in my life. – going to Scotland, and meeting all these great filmmakers. It was part of the program, Black Box: Entangled Experience, which was the experimental program for this festival. The thing about the Edinburgh International Film Festival is I didn't actually submit. I was invited to screen it there, because I had submitted to an experimental film festival that was in Latvia called Process. The programmer there is also involved with the Edinburgh International Film Festival. She saw my film, and I received an email saying I was invited to Edinburgh to screen my film, so that was a really cool thing to happen.

JB: How did they screen your film? On 16mm, or digital?

MR: I got to screen Sir Bailey on film, and there were five other films that were also shown on 16 mm, as well as one 35 mm print. That was really cool. It was so great to have my film travel to Europe and be viewed by an international audience, and to meet other filmmakers at the festival as well. It’s really good to make connections like that, and to be able to visit a city like Edinburgh. The city is so beautiful and everyone is really friendly.

JB: What are you working on now?

MR: I am working on a couple different new techniques using organic film processors. With coffee, grape juice, plants, and stuff like that. I'm also branching out more into colour film. My last four films have been in black and white, and so I want to bring some colour into my work. My dog Brooke, who I also grew up with, passed away on the same day as Bailey. Brooke was a year younger, but she was also very sick. Her liver was failing, and she had to have both of her eyes removed, because of cataracts and pressure building up behind her eye. That's a film that I am working on as well. Sir Bailey was about struggling with an illness, and using a specific technique for that. But with Brooke I want to make a more perceptual film – using color film to explore what Brooke is seeing, or perceiving, or feeling. That’s going to take a while to make. I have tons of different ideas that aren't necessarily fully thought out, but I usually start with a technique, and then I try to find the meaning through that adventure and expand on that feeling through visual representation.

This article appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Splice